Tweet

This week at Infection Landscapes, we will conclude the extended series on gut infections. This final installment will cover amoebiasis. This is another parasitic infection of the gut, but this infection has the potential to cause invasive disease and is associated with greater mortality than the other parasitic gut infection we covered last time, giardiasis. Indeed, amoebiasis is responsible for the world's third highest mortality attributable to a parasite.

Transmission of E. histolytica is by the fecal-oral route with water and food being the primary vehicles of transmission and direct person to person contact playing a secondary, but still important, role. Sexual transmission of E. histolytica is another potential route of transmission when oral and anal sex are combined between an infected and a susceptible individual.

Control and Prevention. Control and prevention of amoebiasis begins by following the usual guidelines: improving sanitation in resource poor areas and maintaining vigilance in personal hygiene. In most settings in the world where amoebiasis is a significant source of morbidity and mortality, improved infrastructure that can maintain adequate water resources is a first priority in its prevention.

Secondarily, personal hygiene at the individual level, especially in the context of food preparation, can also be very important in preventing the spread of E. histolytica: consistent hand washing, boiling water, and thoroughly cooking food are all important in stopping the chain of transmission.

This week at Infection Landscapes, we will conclude the extended series on gut infections. This final installment will cover amoebiasis. This is another parasitic infection of the gut, but this infection has the potential to cause invasive disease and is associated with greater mortality than the other parasitic gut infection we covered last time, giardiasis. Indeed, amoebiasis is responsible for the world's third highest mortality attributable to a parasite.

The Pathogen. Amoebiasis is caused by Entamoeba histolytica, which is another anaerobic protozoan parasite, though E. histolytica is not flagellated:

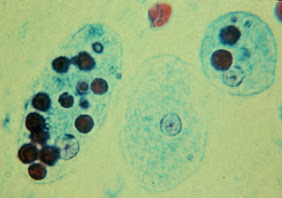

Similar to G. lamblia, the life cycle of E. histolytica is comprised to two distinct stages: the cyst and the trophozoite. As we saw with G. lamblia, infection is initiated when the cysts are ingested and excyst in the gut tract releasing the trophozoite, which is the feeding stage of the parasite. Each successfully excysted cyst will produced 8 trophozoites. These trophozoites migrate to the colon, replicate by binary fission and target the mucous membrane associated with the epithelium of the large intestine. In response to the immunologic pressure of the host, some trophozoites undergo encystation in the colon and pass out of the gut in feces in order to survive and infect new hosts. While the majority of infections are asymptomatic, the pathogenicity of a given organism is strongly influenced by a specific lectin (galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine-specific lectin), which determines the adherence and lytic activity of the parasite. Quorum sensing of the expression of this lectin by other members of the E. histolytica colony, as well as the parasites' interaction with the host's natural microbiome, are also likely involved in the virulence transition. The life cycle of E. histolytica is depicted in the following graphic by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

Another nice depiction of the life cycle by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal that clearly distinguishes between invasive and non-invasive disease is shown here:

Here is simplistic and somewhat over-dramatized animated video depicting the parasite's activity:

Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Two of the trophozoites have ingested red blood cells, which are apparent as dark spots in the endoplasm.

Similar to G. lamblia, the life cycle of E. histolytica is comprised to two distinct stages: the cyst and the trophozoite. As we saw with G. lamblia, infection is initiated when the cysts are ingested and excyst in the gut tract releasing the trophozoite, which is the feeding stage of the parasite. Each successfully excysted cyst will produced 8 trophozoites. These trophozoites migrate to the colon, replicate by binary fission and target the mucous membrane associated with the epithelium of the large intestine. In response to the immunologic pressure of the host, some trophozoites undergo encystation in the colon and pass out of the gut in feces in order to survive and infect new hosts. While the majority of infections are asymptomatic, the pathogenicity of a given organism is strongly influenced by a specific lectin (galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine-specific lectin), which determines the adherence and lytic activity of the parasite. Quorum sensing of the expression of this lectin by other members of the E. histolytica colony, as well as the parasites' interaction with the host's natural microbiome, are also likely involved in the virulence transition. The life cycle of E. histolytica is depicted in the following graphic by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

Another nice depiction of the life cycle by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal that clearly distinguishes between invasive and non-invasive disease is shown here:

Here is simplistic and somewhat over-dramatized animated video depicting the parasite's activity:

The Disease. As mentioned above, the majority of E. histolytica infections are subclincal. In fact, as many as 90% may cause no apparent disease in the infected individual. When infections are symptomatic, disease can range from watery diarrhea to frank dysentery, the latter resulting from an invasive infection of the colon tissue, to severe disseminated disease potentially involving the liver, kidney, spleen, lung or brain. Invasive infection occurs as a result of the trophozoites breaching the mucous membrane of the colon. When this happens, the parasite consume the host cells by phagocytosis in the same way it consumes contents of the gut lumen (bacteria and food particles) in non-invasive infections when it lives commensally with the host. A breach of the protective mucous membrane in the lower intestine results in ulcers and dysentery. Some of these ulcers can be quite severe and lead to the characteristic flask-shaped penetrating holes in the tissue:

If the parasites breach the lower intestinal wall, then they can spread via the circulation and cause disseminated disease in multiple organ systems, which if untreated is often life threatening. The most common disseminated focus of complicated infection is the liver, where abscess formation follows the parasite's invasion of the hepatic tissue:

If the parasites breach the lower intestinal wall, then they can spread via the circulation and cause disseminated disease in multiple organ systems, which if untreated is often life threatening. The most common disseminated focus of complicated infection is the liver, where abscess formation follows the parasite's invasion of the hepatic tissue:

The Epidemiology and the Landscape. Globally, there are approximately 50 million cases of clinically apparent amoebiasis each year, with up to 100,000 deaths. The burden of these cases follows the same geographic distribution as that seen for almost all of the gut infections we have covered in this series: areas with limited sanitation and water infrastructure are the areas where amoebiasis is endemic. And areas with limited infrastructure tend to be the resource poor areas of the developing world. Amoebiasis does indeed occur in developed areas of the world as well, but in these settings it is typically limited to sporadic cases.

Control and Prevention. Control and prevention of amoebiasis begins by following the usual guidelines: improving sanitation in resource poor areas and maintaining vigilance in personal hygiene. In most settings in the world where amoebiasis is a significant source of morbidity and mortality, improved infrastructure that can maintain adequate water resources is a first priority in its prevention.

Secondarily, personal hygiene at the individual level, especially in the context of food preparation, can also be very important in preventing the spread of E. histolytica: consistent hand washing, boiling water, and thoroughly cooking food are all important in stopping the chain of transmission.